The High Risk of Selling Dupes: What Lululemon v. Costco Reveals About Legal Dangers

Dupes: Lululemon v. Costco

We’re all familiar with “knock-off” products intended to resemble luxury or high-end goods but sold at a fraction of the cost—often referred to as “dupes” (short for duplicates). While historically the term “dupe” referenced only legal products inspired by a luxury or brand name product, the term has grown to include a wider range of goods, including goods not so much inspired by a brand name product as they are an exact—or almost exact—copy of another’s goods. Given this expansion, dealing in dupes now gives rise to increased risks of liability and damages. As it becomes increasingly difficult to tell the difference between a dupe and the original, authentic product, the line between what is permissible and what is infringement becomes more difficult to ascertain. With brands adjusting to this growing trend and implementing updated measures designed to identify and eliminate infringing products, the risk of trading in dupes will only continue to grow.

What is a dupe?

In the past, the term “dupe” referred to a product inspired by a brand-name item but not infringing in any way on the rights associated with the brand name. Probably the most classic example is store-brand goods like detergent or pain reliever. True dupes do not bear any marks, designs, or content of another and, therefore, do not infringe on the various IP rights of the name brand product. However, as the stigma associated with purchasing dupes has all but disappeared (particularly with younger generations of consumers), the term has grown to include a wider range of goods, many of which infringe on the various intellectual property rights of the original creator. In fact, in recent years, a number of retailers and platforms have banned use of the term, with Amazon eliminating “dupe” as a search term, TikTok blocking the use of #designerdupe, and Target prohibiting any mention of “dupes” in its marketing materials.

The (Often Unknown) Risks of Dupes

While the market for dupes may be growing, so are the risks associated with dealing in such goods. Many an unsuspecting retailer or small business owner has learned the hard way that dealing in dupes is incredibly risky and can lead to significant monetary damages, the destruction of infringing products, attorneys’ fees, and court costs, damage to the business reputation, and even permanent removal from online marketplaces. Much of the risk comes from a lack of understanding of intellectual property law—and what is, and is not, protected—as well as a lack of attention to how much of the original product has been copied and what potential exists for consumer confusion. Further risk arises from the fact that while federal trademark laws are intended to protect original works of designers and brands and prevent consumer confusion, the permissible interpretation of those laws can be nuanced and lead to unforeseen outcomes for sellers.

Counterfeits

In the modern market, the term “dupe” is increasingly used on what are actually illegal, counterfeit goods. As defined by the Lanham Act, which is the federal statute providing trademark protections, a counterfeit is “a spurious mark which is identical with, or substantially indistinguishable from, a registered mark.” 15 U.S.C. § 1127. Thus, counterfeit goods involve a copy of another brand’s product that bears or is offered for sale in connection with a mark that is identical, or highly similar to, the original brand’s name, trademark, or logo. As indicated in an EU IP Office report issued in 2025:

Currently, illicit trade in counterfeit goods poses a threat to economic growth and innovation, while also threatening public health, safety, and the rule of law. Furthermore, counterfeit trade fuels corruption and organized crime, establishing a vicious cycle where innovation is stifled, consumer trust is eroded, and resources are diverted from legitimate businesses to illicit operations.

See Mapping Global Trade in Fakes 2025, https://euipo.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/observatory/documents/reports/2025_Global_Trade_in_Fakes/2025_Global_Trade_in_Fakes_FullR_en.pdf. The EU IP estimates the value of global trade in counterfeits at a whopping $467 billion, a value illustrating “that counterfeit trade is not a minor problem but represents a major challenge to the integrity of global trade and the sustainability of IP-reliant economies.”

The Cost of Copying: Civil and Criminal Consequences

Trafficking in counterfeit goods can give rise to criminal charges, resulting in jail time and fines. Many name brands work with local, national, and global law enforcement officials as well as the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol and other national and international offices to identify and seize illegal counterfeit goods and bring criminal charges against those dealing in such goods.

On the civil side, an individual found to have trafficked in counterfeit goods can be held liable for three times the total amount of: (i) his or her own profits from the sale of such goods, (ii) any monetary damages sustained by the plaintiff, and (iii) the costs of the legal action. Alternatively, the party bringing a counterfeit claim can elect to recover statutory damages which range from not less than $1,000 or more than $200,000 per counterfeit mark per type of goods for unintentional infringement and not more than $2,000,000 per counterfeit mark per type of goods for willful infringement.

For online businesses, trafficking in dupes that are actually counterfeits has resulted in formal lawsuits (i.e. Apple v. Mobile Star, LLC) as well as the suspension of online accounts, funds withheld from online purchases, and the destruction of inventory—risks expressly noted in Amazon’s seller policies. Likewise, luxury brands regularly bring lawsuits against small boutiques and flea markets for counterfeit sales. Louis Vuitton, known for aggressively protecting its intellectual property rights, has famously sued (and won against) owners of small boutiques and flea markets, including a $3.6 million verdict against a flea market in San Antonio, Texas. See https://www.texasmonthly.com/the-culture/louis-vuitton-knocks-off-san-antonio-flea-market/.

It is important to note that the absence of a seller’s intent to deal in counterfeit goods is not a defense to a counterfeiting claim and does not absolve one of legal liability. Moreover, federal courts in the United States have held that remaining “willfully blind” to the possibility that one’s goods are counterfeit is the legal equivalent to willful infringement, leading to significantly higher damages. That one has offered or sold relatively few counterfeit products, or that others may be offering similar counterfeits in the market, also are not proper defenses to a counterfeit claim and have no bearing on liability. Similarly, that the online marketplace on which the products are offered does not require the seller to verify the authenticity of the goods has no bearing on the seller’s liability to the trademark owner.

Unfair Competition, Trade Dress, Design Patent and Copyright Claims

Many sellers do not realize that trademark infringement can arise even apart from counterfeit goods and that the line between what is permissible—and what is not—is often missed and easily crossed. In addition to prohibiting counterfeit goods, the Lanham Act also gives rise to claims for unfair competition and trade dress infringement. Similar protections exist for designs that have been patented and content that is subject to copyright.

Unfair Competition

Section 43 of the Lanham Act provides for a federal cause of action for unfair competition and covers a wide range of claims, including false advertising, false endorsement, false designations of origin, false descriptions, and reverse passing off. Courts have interpreted this Section to address a wide range of deceptive practices, the key inquiry of which is always the likelihood of consumer confusion or deception, which is the basis for determining liability. These protections extend to both registered and unregistered trademarks and trade dress alike, offering protection against deceptive practices that mislead consumers about the source or sponsorship of a product. An unfair competition claim may arise any time a product bears enough similarity to the distinctive elements of another’s work to cause consumer confusion as to the source of the goods. This includes initial interest confusion, where a consumer is initially attracted to a product based on distinctive elements that mirror those of the original good, even if the consumer later realizes (even before making a purchase) that the product is a dupe and not an original. This type of confusion is particularly significant in online situations, where consumers may be misled by search engine results or advertisements.

Trade Dress

Trade dress protection is also governed by the Lanham Act and safeguards the total image or overall appearance of a product, which may include features such as size, shape, color, texture, graphics, and packaging. Trade dress serves to identify the source of a product or service, much like a trademark. The purpose of trade dress protection is to secure the goodwill of the business and to help consumers distinguish between competing producers. Trade dress can be protected by federal registration with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) but can also arise without federal registration under the common-law.

Design Patent

A design patent protects the aesthetic, ornamental, or non-functional aspects of a product’s design and one who owns a design patent has the exclusive right to use those patented aspects of the design. Sellers of dupes run the risk of patent infringement when they offer products that are substantially similar to the patented designs of others. This can include the distinctive shape of a handbag (i.e., the Wal-Mart knockoff of the Hermes brand Birkin bag, known as the “Wirkin”), or ornamental designs included on apparel, as discussed below.

Copyright

Dupes, and particularly fashion dupes, also run the risk of infringing copyrights. In this context, copyrights may exist to protect a specific fabric print or jewelry design, increasing the risk of infringement if a dupe product is too similar to either. Like trademark damages, a seller found liable for copyright infringement may be required to pay “the actual damages suffered by him or her as a result of the infringement, and any profits of the infringer that are attributable to the infringement and are not taken into account in computing the actual damages” or statutory damages. Statutory damages can range from not less than $750 or more than $30,000 per work for non-willful infringement and as much as $150,000 per copyrighted work for willful infringement. And requiring a seller to pay the attorneys’ fees and court costs of the copyright owner is the rule rather than the exception in copyright cases. 17 U.S.C. § 504.

Lululemon v. Costco: A Cautionary Tale

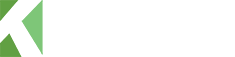

In a case highlighting many of these risks, athleisure giant Lululemon recently filed a lawsuit against Costco in the Central District of California, claiming trademark (trade dress) infringement, unfair competition, and design patent infringement. Lululemon maintains that Costco’s offering of various jackets, hoodies, and men’s pants under its private label Kirklandâ brand and other third-party branding infringes on Lulu’s intellectual property rights. Specifically, Lululemon alleges that Costco is offering a half-zip hoodie that infringes Lulu’s design patents in its Scubaâ hoodie by copying the wavy ornamental designs on the side and front of the jacket as protected by federal patent law and state common law:

Lululemon also claims that Costco allegedly used Lulu’s Scubaâ trademark in the description of its product on its website.

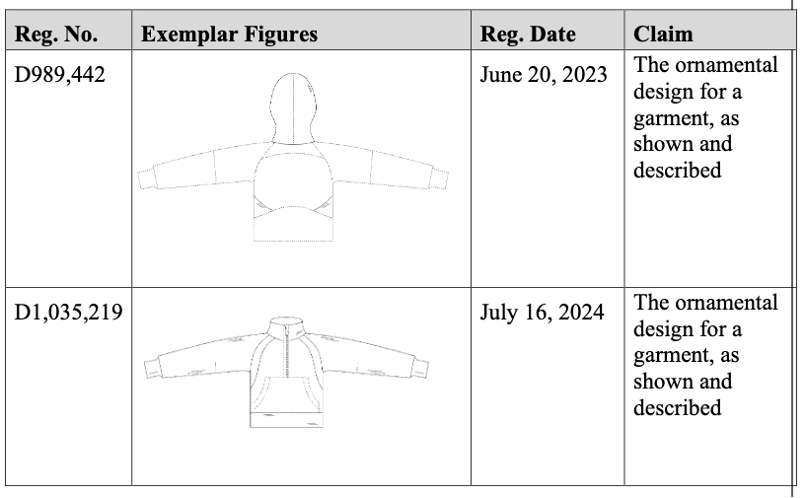

Separately, Lululemon asserts that Costco is offering low-price versions of an athleisure jacket that infringe on Lulu’s trade dress registrations covering wavy ornamental lines on the front and back of its Defineâ jacket.

Finally, Lululemon claims Costco’s “dupes” violate Lulu’s trade dress in its ABC pants for men, also based on the copying of ornamental lines on the Costco dupe, as well as infringement of Lulu’s trade dress in its “Tidewater Teal” color.

Learning from Lululemon’s Legal Strategy

In support of its claims, Lululemon highlights that Costco is “known to use manufacturers of popular branded products for its own Kirklandâ ‘private label’ products” that could lead consumers to believe that the Kirklandâ products are made by the same suppliers of the original items they are replicating and that Costco “does not dispel this ambiguity.” Moreover, Lululemon maintains, while “some customers incorrectly believe these infringing products are authentic Lululemon apparel,” still others are drawn to and purchase the products simply because they are difficult to distinguish from the original Lululemon items. In fact, Lululemon pleads, one of the reasons retailers even desire to sell dupes is because of the potential for confusion and the perceived connection between dupes and the authentic products they copy. Thus, “one of the purposes of selling dupes is to confuse consumers at the point of sale and/or observers post-sale into believing that the dupes are [the trademark owners’] authentic products, when they are not.” Lululemon asserts that this piggybacking on the goodwill of established brands is clear infringement that cannot be allowed to continue.

In all, Lululemon asserts 8 separate causes of action under the Lanham Act, 3 under California state law, and 1 patent law claim and seeks monetary damages (including three times Costco’s profits from the allegedly unlawful sales nationwide), a permanent injunction, and the recovery of its attorneys’ fees and costs incurred throughout the pendency of the action.

While the case is still in its infancy and it is unknown whether the parties will be able to reach a pre-trial settlement, at best, Costco will bear significant legal costs even if it is ultimately successful in settling or defending the case. At worst, Costco could be on the line for heavy monetary damages and the inability to offer the remainder of its inventory for sale to the public, not to mention damage to its business reputation and legal fees (its own, as well as those incurred by Lululemon).

A prior case, filed in 2018, may provide helpful guidance to Lululemon in presenting its claims. Gavrieli Brands, the maker of Tieks ballet flats, brought a lawsuit against Soto Massini which resulted in a $2.1 million jury award for trade dress infringement. Of particular import in that case was Massini’s deliberate targeting of consumers of Tieks authentic brand ballet flats through a direct marketing campaign on Facebook to sell the “duped” product. Gavrieli argued (and the Court agreed) that this was evidence of a deliberate intent to sell a look-alike product to the same consumer base, supported the existence of likely consumer confusion, and was intended to divert sales from Tieks to Soto Massini.

Other Legal and Ethical Concerns

In addition to the intellectual property traps discussed above, dealing in dupes exposes businesses to other legal and ethical concerns, including state and federal false or misleading advertising claims and statutes intended to prevent deceptive trade practices, as well as product liability claims arising when products cause harm or injury to consumers (particularly when questionable or “low cost” manufacturing practices are involved). The dupe industry also gives rise to legitimate concern about the stifling of creativity and innovation in the marketplace, as well as environmental protections related to the manufacture and production of inexpensive dupes (often in other countries with less stringent protections) and unethical labor practices, such as sweat shops and unethical child labor.

Final Thoughts: Is Selling Dupes Worth the Risk?

While dupes are a growing trend, dealing in dupes comes with significant risk, much of which is likely unknown to sellers looking to profit from the practice. Whether a fabric print is protected by copyright, the shape of a pair of glasses by design patent, or the color scheme or design of an article of clothing by trade dress, the seller may be unaware of that protection, especially since some forms of protection are harder to identify. Still, the risk of liability remains. And the more similar or “better” the dupe, the greater the risk. Even counterfeit goods have been lumped into the “dupe” craze, bringing additional risk of both civil—and criminal—liability. The recent lawsuit filed by Lululemon against Costco highlights these risks as well as the true purpose of the dupe trend: piggybacking on the goodwill of established, higher-end brands. At the end of the day, sellers should beware: the risk is significant and may be largely unknown.

Klemchuk PLLC is a leading IP law firm based in Dallas, Texas, focusing on litigation, anti-counterfeiting, trademarks, patents, and business law. Our experienced attorneys assist clients in safeguarding innovation and expanding market share through strategic investments in intellectual property.

This article is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. For guidance on specific legal matters under federal, state, or local laws, please consult with our IP Lawyers.

© 2026 Klemchuk PLLC | Explore our services