The Federal Trademark Registration Process Is More Complicated Than Ever

The Federal Trademark Registration Process Is More Complicated Than Ever. Here’s How to Maximize Your Chance of Success

If it seems to you that the process of obtaining federal trademark registration has become more complicated and time-consuming in recent years, you are not alone. As an initial matter, an almost 28% increase in the number of applications in 2021 (likely due to COVID) created a backlog at the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). This means it can take as long as 6 to 9 months before an Examiner first reviews a new application. Still further, the number of applications that successfully navigate the process to registration has been declining—from 59.22% in 2019 to 48.49% in 2023. This lower success rate is reflective of any number of factors, including the increased complexity of the process itself as well as more rigorous standards of review. For most businesses, this begs a number of questions: (1) is federal trademark registration worth it? and (2) How can businesses maximize their chance of success in obtaining federal trademark registration?

Federal Trademark Registration Provides the Greatest Level of Protection for Your Brand

In the United States, trademark rights arise out of use rather than registration. This means that a company maintains trademark rights in a mark the moment that mark is used to identify the company’s goods or services in commerce. These initial rights—apart from federal registration—are known as common-law trademark rights. Under the common law, he who first uses a mark in commerce (in a specific geographic area) has the right to protect the mark in that area. This can be local, regional, or nationwide use. The protections afforded common-law trademark rights are somewhat limited, however. A trademark owner can send cease and desist letters and can even file a lawsuit to enforce its rights, but without a federal registration may be limited in any recovery of damages. Moreover, a business seeking to enforce common-law rights in court will be required to provide additional evidence of (1) ownership of the mark; and (2) the protectability of the mark.

One who holds a federal trademark registration, on the other hand, is not limited in the recovery of infringement damages and a federal registration certificate constitutes prima facie evidence of both the ownership and protectability of a mark. A federal registration also acts as nationwide notice of the owner’s rights in the mark, opens avenues of enforcement with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (for goods), and allows for enhanced enforcement mechanisms online, such as the ability to take down an infringing website or post. Federal registration is also vital in instances in which a company (or certain of its assets) are to be sold.

Given that federal registration is preferred (if not necessary) for most businesses, the best strategy is to identify and implement tools to help maximize both efficiency and success in obtaining federal trademark registration.

Understanding the Federal Registration Process

In order to maximize one’s chance of successfully registering a federal trademark, one must first understand the basic registration process. A trademark is any word, name, symbol, device, or combination thereof used in commerce to identify and distinguish the source of goods or services of one party from those of others. A trademark that consists of only words is called a “word mark,” while a trademark that is made up solely of a design or logo is a “design mark.” A mark that includes both words and a logo or design is a “word + design mark.” Once a mark has been selected (discussed in greater detail below), an application must be completed and filed using the USPTO’s online filing system. In order to complete a federal trademark application, you will need the following information: a description of the mark, the full name and physical address of the owner of the mark (P.O. Boxes are not accepted), a description of the goods or services on which the mark is or will be used, the date the mark was first used in commerce, and clear evidence of that use in commerce (if filing an in-use application). Still further, the trademark owner (or representative of the owner) will need to sign a declaration confirming the accuracy of all information in the application and confirming no knowledge of any other party who has first rights in the mark.

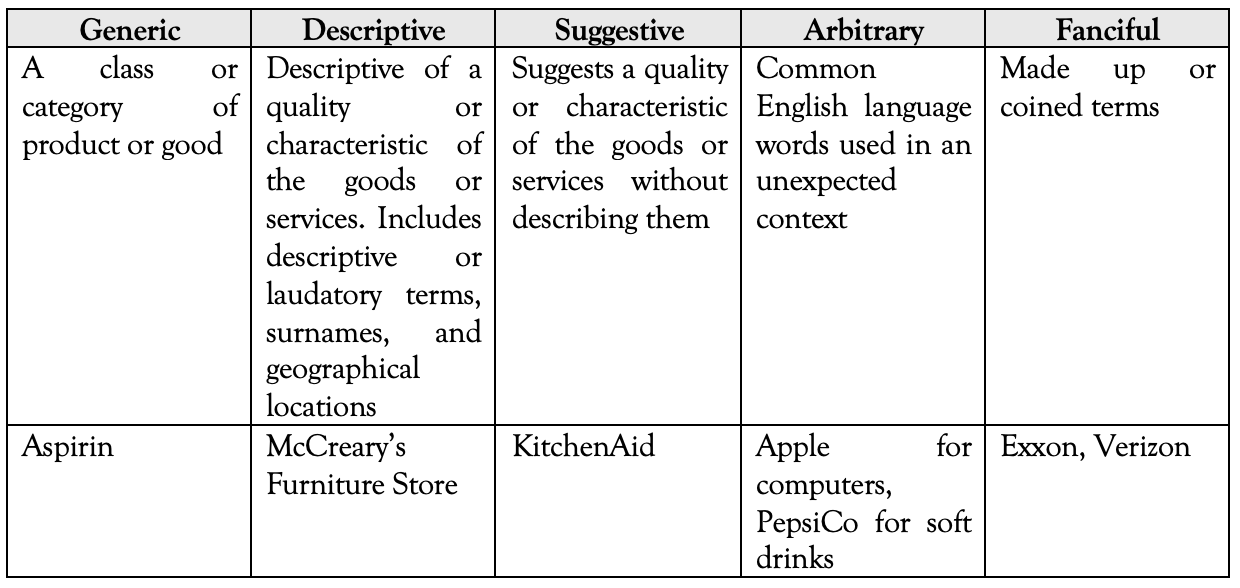

After an application is submitted, the USPTO will assign an Examiner to begin the review process. In reviewing the application, the Examiner is limited to what information is contained within the actual application (as opposed to what is on a company’s website or product packaging). While an Examiner will review a pending application to ensure general compliance with USPTO filing requirements, he or she will also consider (1) whether the mark is protectable as a trademark; and (2) whether the mark, as described in the application, is likely to cause confusion with any existing registration for the same or a similar mark (the “likelihood of confusion analysis”). If the Examiner determines that the mark as identified cannot be registered as a trademark (i.e., it is generic or descriptive of the goods and services), the Examiner will issue an office action detailing the nature of the refusal to register. Office actions issued early on in the process are called “Non-Final” while final determinations are issued as “Final” office actions. If Non-Final, the trademark owner will have the opportunity to respond to the office action in writing and challenge any conclusions made by the Examiner. If Final, the owner must either file a Request for Reconsideration (to add any additional evidence to the record) or appeal to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB).

If there are no concerns, or if arguments offered in response to a Non-Final office action are accepted, the Examiner will allow the application to proceed to the Publication phase. This means that the mark is included in a federal publication of pending applications as a means of providing notice to the public of what marks may proceed to registration. This allows third parties to object to an application (even if the Examiner noted no third-party conflict). If there are no objections during the 30-day Publication phase, then the mark will proceed to registration.

Tips for Maximizing Your Chance of Success at the USPTO

With regard to the general process outlined above, only 43% of federal trademark applications make it from application to registration with no issues. That means that a whopping 57% of all applications filed will encounter some level of rejection before proceeding to registration, if they even get to registration at all. The good news is that there are tangible ways to increase your chance of getting to registration with as few hurdles as possible.

1. Work with trusted IP counsel

In addition to the standard difficulties associated with federal trademark registration, the USPTO recently updated its online filing system from the former TEAS system—which is now retired—to a new Trademark Center as the mandatory interface for filing trademark applications. The new Trademark Center can be used by non-attorneys but requires compliance with its ID.me Verification Protocols including the creation of a USPTO.gov account and biometric verification. Still further, the “Custom Identification” element of Trademark Center can further complicate the application and prosecution process. While it allows an applicant to select pre-approved descriptions (for a lower application fee), use of the Custom Identification tool increases the risk the description does not accurately reflect an owner’s goods or services, leading to a rejection of the description and increased fees and prosecution time. Indeed, since the implementation of the new Trademark Center, applications filed using the “Custom Identification” element appear to be experiencing an increased rate of initial refusal. Even if the “Custom Identification” tool is used and an application proceeds to registration without incident, it can result in inadequate protection and an increased risk of cancellation. Working with trusted IP counsel will help to ensure that your application has an appropriate and accurate classification and description and will save you the additional time and hassle of navigating the USPTO’s system.

Even beyond the actual filing of the application, working with trusted IP counsel from the beginning can ensure adherence to each of the tips outlined below, saving you both time and money in the long run. This is particularly true if an office action is issued or a third-party files an objection to your application, as IP counsel are well versed in the specific rules and regulations that apply to trademark prosecution with the USPTO and TTAB.

2. Choose a strong mark

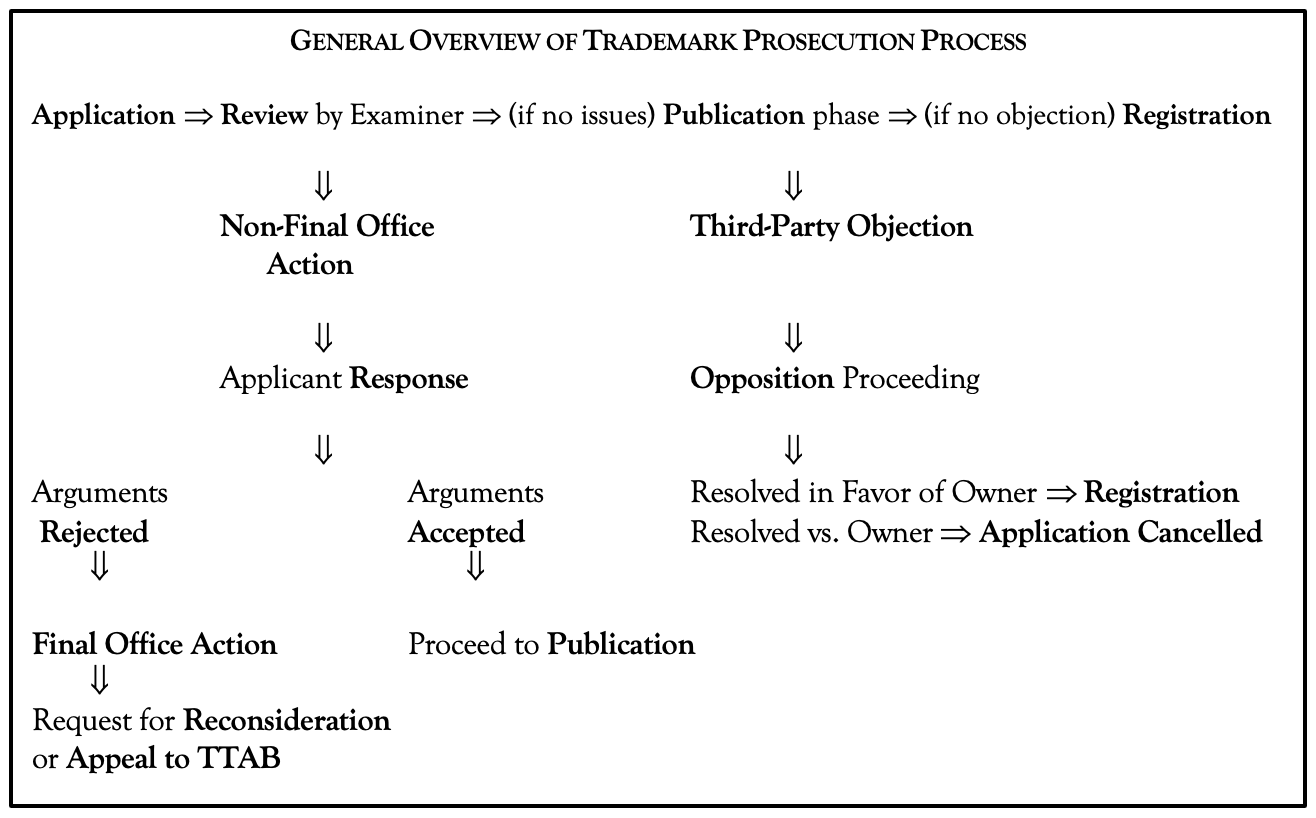

One of the most important ways to maximize success in obtaining a federal trademark registration – while minimizing the risk of delay and increased expense – is to choose a strong trademark. Importantly, a “strong” trademark from a marketing perspective is not necessarily the same as a strong mark for federal registration purposes. Marketing experts typically prefer the use of short, common terms that allow consumers to easily identify the nature of the goods or services offered. But for federal registration purposes, these are not only some of the weakest marks, but they are also largely taken, having been previously registered by third parties. Under trademark law, the strength of a mark is determined by a sliding scale that ranges from genetic to fanciful, as shown below.

For example, in the context of an automotive shop, the sliding scale could look like this:

Generic: Automotive Shop

Descriptive: World’s Best Auto Shop

Suggestive: Greasy Gloves

Arbitrary: Double Barrel

Fanciful: Arbo

Under trademark law, generic marks cannot be registered under any circumstance. Descriptive marks also are unregistrable unless the owner can demonstrate acquired distinctiveness – meaning, that the mark has been in use (and advertised, marketed) in commerce for a long enough period of time and to a sufficient degree that consumers have come to associate the mark as identifying the owner’s goods or services. By statute, such use must have been continuous and ongoing for at least five years. In practicality, Examiners often require more than just five years’ use to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness. Thus, while generic or descriptive marks are preferable from a marketing standpoint, they are often unregistrable or require significant expense and time to reach registration. Even upon registration, these types of marks are so weak as to be difficult to protect and enforce.

Suggestive, arbitrary, and fanciful marks, on the other hand, may require more marketing at the outset to allow consumers to connect the mark with the goods or services, but are more easily registered and offer the most protection in the long-term, creating a more valuable business asset overall. While this has always been the case, the relative crowding of the USPTO’s Principal Register has come to highlight the importance of a stronger mark. For example, one who attempts to register Creamy for an ice cream shop is practically guaranteed a refusal—because “Creamy” is descriptive (if not generic) and will have to be disclaimed. The applicant in that scenario should expect numerous filings with the USPTO over many months to attempt to even reach Publication, where it is likely to face challenges by the owners of any number of other “Cream” or “Creamy” marks. On the off chance it were to register (perhaps because the application included a distinctive logo along with the wording) it remains a weak trademark and will be difficult to protect and enforce given the crowded field of “Creamy” trademarks. That same applicant could expect a much less complicated and costly process were he to apply to register Moo-Moo (suggestive), Farmer’s (arbitrary), or Zolato (fanciful) (assuming there are no prior registrations for that mark in the context of ice cream) and would have much less difficulty protecting such a mark, resulting in a more valuable business asset.

3. Begin with a Trademark Search

Given the potential for conflict, it is always a good idea to start any trademark registration (or even selection) process with a basic trademark search. Searches can be conducted internally or, for more comprehensive searching and analysis, by IP counsel. A basic trademark search covers a number of important bases: (1) as due diligence to ensure that any trademark you may be using does not infringe on any existing mark or federal registration, potentially saving you litigation or rebranding expenses down the road; (2) to identify existing registrations that could prevent you from registering a proposed mark or that could add complexity to the trademark prosecution process; and (3) to identify the level of “saturation” in the market and on the Principal Register for the proposed mark (which will have bearing on the mark’s registrability as well as its protectability). Early on, a less comprehensive kind of “knock out” search can be used at the initial trademark selection phase to eliminate from consideration those marks that immediately show to be problematic. Understanding the lay of the land on the Principal Register can provide key insights that allow you to tailor your mark and/or application to try and avoid refusal or, at a minimum, increase your chances of overcoming an initial refusal and circumventing conflict with third parties who own similar marks. This is particularly true in light of descriptiveness and likelihood of confusion refusals.

Descriptiveness Refusals

One of the more important pieces of information to be gleaned from a proper trademark search is the likelihood that an Examiner at the USPTO will consider a proposed mark to be unregistrable as “merely descriptive of a characteristic or quality” of the stated goods or services. If a proposed mark describes a single aspect of the goods or services, that may be sufficient for the Examining Attorney to find that the trademark is merely descriptive. Descriptiveness as relates to a potential trademark can take many forms, including a surname (as in the McCreary example above), a geographical location, or a laudatory phrase (World’s Best, Original). Still further, however, descriptiveness is determined in accordance with the description of goods or services included in an application. For example, a trademark application for IOT with respect to a good or service specific to the Internet of Things is likely to be deemed descriptive. Thus, if a proposed mark includes a term that is considered an “industry term,” it will be rejected as a means of ensuring all who participate in that industry also have use of that term.

Descriptive marks can achieve federal registration if they have acquired distinctiveness, meaning the mark has been in use in connection with the same goods or services for at least five years and has gained widespread recognition as the source of the mark owner’s goods or services. The more descriptive the mark, the more evidence is required to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness, such as many years of use, significant expenditures on marketing and advertising, and significant media exposure. Such marks, however, often remain weak and are more difficult to enforce against third-party infringement—even after registration—as the USPTO and most courts are keen to protect common words and industry terms for use by all.

Likelihood of Confusion – 2(d) Refusals

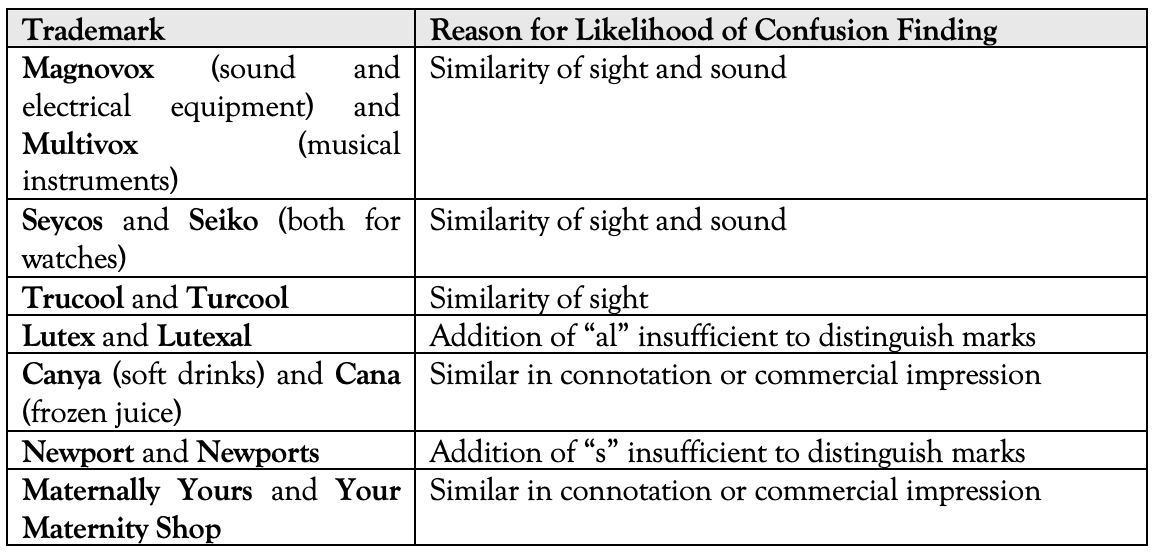

The more common—and indeed primary—reason for the refusal of a trademark application is a finding that the pending application is likely to cause confusion with an existing registration. Refusal on this basis is subject to Section 2(d) of the Trademark Act and is often referred to as a “2(d) refusal.” There are many factors that can suggest a likelihood of confusion, but the two most commonly addressed by the USPTO are (1) the similarity of the marks and (2) any similarity of the goods and services, either of which can lead consumers to mistakenly believe the goods or services come from the same source as the registered mark. If a similarity in either respect is deemed sufficient to result in consumers mistakenly buying goods or services other than what they intended or creating the mistaken belief that one company’s goods or services are sponsored by or affiliated with another company, when in fact they are not, the mark will be issued a 2(d) refusal.

Trademarks do not have to be exactly the same to give rise to a likelihood of confusion. Rather, there need only be some similarity in sight, sound, or connotation. Similarity in sound means the two marks sound the same when spoken, even if they are spelled differently. Similarity in sight includes the use of the same or similar terms or design or similar starting and/or ending terms. And similarity in connotation means the marks convey the same overall commercial impression or meaning. Importantly, minor differences between the marks, such as changes in letters or punctuation, spacing, or the addition or removal of descriptive terms is insufficient to demonstrate sufficient distinction between the marks. For example, FUN FAB FIT was deemed likely to cause confusion with FAB FIT FUN even though the words were in a different order. In re FabFitFun, Inc. (2023). While trademarks must be viewed as a whole, one basic rule is that the Examiner should focus more on the dominant (or source-identifying) portion of a mark when determining similarity of marks. This is because the dominant portion is that most likely to make an impact on and be remembered by consumers. See In re Detroit Ath. Co., 903 F.3d 1297, 1303 (Fed. Cir. 2018) (finding DETROIT ATHLETIC CLUB likely to cause confusion with DETROIT ATHLETIC CO., both for sports apparel, because “club” and “co” are descriptive terms). The Trademark Manual Examining Procedure (TMEP) guide under §1207.01(b) has more information about how to evaluate similarities between marks.

Relatedness of the goods or services is based on whether the goods or services are related in a way that consumers would expect them to come from the same source and is determined based on the language included in the relevant application and registration, regardless of actual use in the marketplace. Likelihood of confusion can apply to goods versus goods, goods versus services, and services versus services. Thus, while there is no per se rule that certain categories of goods or services are similar to others, the USPTO has found similarity in cases involving clothing (Int. Cl. 25), jewelry (Int. Cl. 14), or cosmetics (Int. Cl. 1, 3); business consulting (Int. Cl. 35) and software (Int. Cl. 9, 42); or restaurant services (Int. Cl. 43) and food stuffs (Int. Cl. 30) or beverages (Int. Cl. 32 or 33). Moreover, the more similar the marks, the less similar the goods or services need be in order to find a likelihood of confusion.

Because likelihood of confusion refusals can be quite difficult to overcome—recent statistics from the USPTO show that 90% of 2(d) refusals are upheld on appeal to TTAB—it is important to incorporate trademark searches into the mark selection process or at least prior to applying for registration, so that an informed business decision can be made about the chance of success for any given application in light of existing registrations.

4. Maintain and provide evidence of clear, consistent use in commerce

As noted above, trademark rights in the U.S. arise out of use, which means that no mark can obtain federal registration without use in commerce. “Use in commerce” for purposes of federal registration means the actual, ordinary-course-of-trade sale or transportation of goods—or rendering of services—bearing a trademark across state lines or internationally. The evidence necessary to demonstrate use in commerce is different depending on whether the mark is used in connection with a good or a service. For goods, use in commerce is often demonstrated by use of the mark on the product or packaging in actual sales to consumers in more than one state. For services, use is regularly shown through inclusion of the mark on brochures, advertising, invoices, or other consumer-facing uses in more than one state. Use on a website can work for either goods or services, provided there is a “point-of-sale” page that displays the mark and where consumers can purchase or contact the company to purchase the relevant good or service. Such use will need to be documented and provided in connection with an in-use trademark application or, if filing an intent-to-use application, will need to be submitted once the application has undergone initial review and has been “allowed.”Even after registration, ongoing and consistent use of the mark as shown in the trademark registration is necessary to preserve the registration and protect against any infringement. Use of a standard word mark that has no stated limitations can be in any color, font, or size and still conform to the registration. Use of a design mark must appear exactly as in the registration certificate. Anything other than nominal change in a design is considered a material change and results in a new mark. For example, if the registration certificate shows the logo to the left of the words in a word + design mark, use of the logo below the words would constitute a material change and would not support ongoing use of the mark as registered.

Maintaining consistent use has become even more important in recent years, as the USPTO has begun conducting annual audits of existing registrations to confirm they remain active and in use (even before they are due for renewal). By way of example, on January 27, 2026, the USPTO issued a show cause order listing 3,361 existing applications and registrations that will be stricken from the register unless the owners can show cause why the application/registration should be maintained. Recent audits by the USPTO have resulted in the cancellation of registrations for lack of use but also for fraud in the application or prosecution process (sometimes tied to inaccurate representations of use or other types of fraud on the USPTO).

5. Identify the proper Class(es) of Goods or Services – for now and for later

Another means of ensuring success in the federal trademark registration process is to accurately categorize your goods or services within the various USPTO categories, known as International Classes. A list of the USPTO International Classes can be found here: https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/basics/goods-and-services. Classes 1-34 pertain to goods, while Classes 35 – 45 are for services. Properly categorizing and describing your goods or services can minimize the risk of your application being rejected early on.

It is also important to clearly identify those classes of goods in which you may already have use, as opposed to those that you may begin to use in the not-so-distant future and those that may be required further down the road. For marks already in use, an in-use application is the most efficient form of application. For those categories in which the mark may soon be in use, an intent-to-use application will allow you to apply for and provide notice of your intent to use the mark in those categories. With intent-to-use applications, an Examiner will review the mark and its intended use and, if acceptable, will designate the mark “allowed.” The owner of the mark will then be required to show use of the mark in those categories in order for the mark to proceed to registration. If the mark will not be used on certain categories of goods or services for a longer period of time, you will want to wait and file an application for those classes as you get much closer to actual use (i.e., within a year). Regardless, it is important to include all possible classes of use in any pre-application trademark search and to continue to monitor any identified third-party use in those classes. You don’t want to file and register a brand in a few classes only to later discover that you cannot expand into other categories due to pre-existing third party registrations.

6. Budget time, expense, and energy for a longer prosecution process

Overall, while the importance and benefit of federal trademark registration remains paramount, the trademark prosecution process has become more complicated—and crowded. With any application for federal trademark registration, be sure to budget the time, expense, and energy for a longer prosecution process. The current wait time from the filing of an application and the initial Examiner review is 6-9 months, with the complete process taking 12-18 months on average. Likewise, since less than half of all federal trademark applications proceed to registration without any significant hurdle or refusal, anticipating at least some level of initial refusal and argument with the USPTO Examiner can help manage internal company expectations and budgets and leave you better prepared for the process.

Klemchuk PLLC is a leading IP law firm based in Dallas, Texas, focusing on litigation, anti-counterfeiting, trademarks, patents, and business law. Our experienced attorneys assist clients in safeguarding innovation and expanding market share through strategic investments in intellectual property.

This article is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. For guidance on specific legal matters under federal, state, or local laws, please consult with our IP Lawyers.

© 2026 Klemchuk PLLC | Explore our services