What Coca-Cola Teaches about Trade Secrets versus Patents in Selecting Intellectual Property Strategies

Choosing between Patent Protection or Trade Secret Strategy? The Coca-Cola Story May Provide Valuable Insights on this Strategic IP Law Choice.

Coca-Cola’s Strategic Decision to Pursue Trade Secrets over Patents Built a Dynasty

Coca-Cola, one of the world’s most recognizable brands, reaches millions of people each day. Despite competitors trying to replicate the taste, Coca-Cola has remained unique — making it one of the most valuable brands in the world. But why do people love Coca-Cola so much? Is it all about the taste? Some say that the secret formula has become as much of an asset as the drink itself. The choice to keep their formula a trade secret rather than securing patent protection has kept it exclusive for over 135 years and makes it a pioneer in IP strategy, with valuable lessons for today’s businesses, both large and small. But to understand the Coca-Cola story and its trade secrets over patents strategy, we need to step back to an unlikely place — Atlanta, GA in the 1880’s.

What can the 135-year secrecy of Coca‑Cola’s formula teach modern businesses about protecting innovation? It all starts with a key IP decision…

John Pemberton and the Invention of the Coca-Cola trade secret recipe

Let’s say you want to experience first-hand the city of Atlanta in the 1880s. You go back in time to see the rough beginnings of the city’s first sewer and water systems, with unsanitary waste lining the sweltering city’s unpaved streets. By this time, Atlanta had surpassed Savannah as Georgia’s largest city. It was also the first to enact prohibition, a law cheered on by the city’s reformers, but resented by many working-class residents and Civil War veterans. You step out of the heat and into Jacobs’ Pharmacy. With alcohol banned, Atlantans now searched for a new way to unwind and cool off, and many pharmacies became the answer. More than just a place to fill prescriptions, Jacobs’ Pharmacy was one of these popular places and offered cooling “fizzy tonics with syrup.” It was also the first place to serve the syrupy carbonated tonic that would captivate the globe—Coca-Cola. The recipe, still in its infancy, was formulated by John Stith Pemberton for a surprising reason.

Pemberton, a Confederate Civil War veteran, developed a dependence on morphine after sustaining an injury during battle. Like many other veterans, he had no other option for pain relief and wished for a gentler alternative. A pharmacist by trade, Pemberton searched for a safer way to ease his pain without the addictive side effects. His earliest recipe, Pemberton’s French Wine Coca, combined coca leaf extracts with kola nuts and alcohol. After prohibition, however, Pemberton removed alcohol from the beverage and mixed it with carbonated water, creating Coca-Cola.

A glass of Coca-Cola cost only five cents and was advertised as “delicious and refreshing.” These days, a five-cent drink sounds like the company giving their product away, but in the 1880s it was priced as an affordable indulgence—something that was seen as nice and classy, yet affordable enough for people to buy each weekend. The signature Coca-Cola name and iconic script logo were both created by Pemberton’s bookkeeper, Frank Robinson, and are still recognized today. Few imagined that the fizzy drink served at Jacobs’ Pharmacy would become the global icon it is today—a symbol of innovation, cooling refreshment, and American culture itself.

The $300 Sale: How Asa Candler Acquired the Coca-Cola Formula

You may think that inventing Coca-Cola would make you a rich entrepreneur, giving you both fame and fortune. In Pemberton’s case, however, you’d be wrong. Pemberton faced mounting medical bills from his declining health — he had stomach cancer in addition to his Civil War injury and morphine addiction. He began to sell shares of Coca-Cola to pay his medical bills in what some have called a “fire sale.” Though multiple people held small shares in the company, a businessman named Asa Candler bought them out, beginning in 1888, and eventually acquired majority control by 1891. Initially, Candler bought his shares from Pemberton for a mere $300 (about $10,400 in today’s money). When Pemberton passed away at the age of 57 in August 1888, he was destitute, never having the opportunity to see the success of his brand.

In contrast to Pemberton, who was focused on the medicinal aspects of the drink, Asa Candler had a larger vision for his brand. A strong believer in marketing and wanting mass appeal, Candler sent out coupons offering a free sample of Coca-Cola and shifted the brand’s identity from “tonic” to “refreshing beverage.” Not only was Candler credited as one of the first in U.S. history to offer coupons for free product samples, he also heavily invested in distribution—enabling the spread of Coca-Cola far beyond Jacobs’ Pharmacy. Candler placed Frank Robinson’s distinctive script logo on anything he could—calendars, soda fountains, clocks, fans, and signs—creating consistent brand visibility. By 1895, Coca-Cola was sold in every U.S. state, cementing its place as a national brand. Candlers’ marketing laid the groundwork for Coca-Cola’s intellectual property rights strategy.

Coca-Cola quickly grew from a regional product, served only in Atlanta, to a nationally recognized brand. Demand skyrocketed as soda fountains became a core part of American culture, making Coca-Cola a staple refreshment. Candler built Coca-Cola into a household name, making it synonymous with refreshment and trust while laying the foundation for the company to grow into a global superstar.

Coca-Cola’s Rise to a Global Brand Through Marketing and IP Strategy: Building a brand around the coca-cola trade secret

Advertising expanded, and Frank Robinson’s script logo became the company’s visual identity, appearing on everything from newspapers and calendars to billboards and bus stop benches. Coca-Cola’s logo and its slogan, “Delicious and Refreshing,” became central to the company’s identity.

Coca-Cola Brand Protection

Nationwide success also brought new challenges. Coca-Cola began protecting its name and logo early on, combating counterfeiters and copycats. Specifically, copycat colas were being sold in bottles that looked similar to the straight-sided bottles Coca-Cola used at the time, tricking customers into thinking they were buying the real Coca-Cola. To combat this, Coca-Cola began its trademark protection by deciding to switch to a bottle so different from its competitors that it was instantly recognizable and nearly impossible to knock off. In 1915, Coca-Cola launched a design contest for a bottle so distinctive people could recognize it “in the dark or by touch.” The Root Glass Company of Indiana won the contest with a design by Earl R. Dean. Dean modeled the bottle after a cacao pod he had seen in an encyclopedia, and even though Coca-Cola doesn’t contain cocoa, the shape has become iconic.

Coca-Cola also began spreading overseas in the early 20th century, with a huge boost coming during World War II. In 1941, Coca-Cola’s president pledged that every American service member would be entitled to a five-cent Coke, wherever they were in the world. To keep that promise, the company worked with the U.S. War Department to set up bottling facilities near military bases in war zones, which the War Department saw as a morale booster — reminding soldiers of home and providing comfort. These soldiers carried Coca-Cola throughout the world, spreading brand recognition and making it a global American symbol. By the end of the war, 64 bottling plants had been built overseas, laying the foundation for global expansion and showing how the company’s global brand strategy used a combination of IP and marketing.

These days, Coca-Cola is sold in over 200 countries, with billions of servings consumed each day. Since its expansion, it has consistently been one of the most valuable and recognizable global brands. From humble beginnings, it has grown into a worldwide cultural phenomenon. Yet, as Coca-Cola rose to fame, one mystery stood out from the rest - the secret formula that the competition could never replicate. See Coca-Cola Company Official History for more details.

Legal and Practical Efforts at coca-cola recipe protection

The secret formula, known internally as Merchandise 7X, has remained a trade secret to this day. The ingredients listed on the product label are public knowledge (carbonated water, sugar, caffeine, caramel color, phosphoric acid, etc.), but the blend of flavoring oils that creates the signature taste has never been released or successfully replicated. The company uses this secret to build mystery around the product, giving consumers the sense that they’re drinking something special.

Over the decades, conspiracy theories have surrounded the secrecy of Coca-Cola’s formula. Some claim the soda still contains cocaine, others believe it includes addictive “mystery” ingredients, that the formula has quietly changed over time, or that the company is hiding controversial ingredients. Coca-Cola has never discouraged these rumors. In reality, the trade secret itself has become an indispensable marketing weapon, creating mystique and building brand loyalty. In 2011, the company moved the formula from its SunTrust bank vault, where it had been stored since 1925, to a vault at the World of Coca-Cola in Atlanta — staying true to its strategy of using secrecy as a powerful marketing tool.

Competitors have tried and failed to duplicate Coca-Cola’s flavor for decades. So, why has the company kept its formula a trade secret instead of patenting it? Unlike patents, trade secrets that a are properly protected never expire. But protecting the unique taste isn’t the only reason for keeping it secret — Coca-Cola’s formula is considered one of the most valuable trade secrets in history, a selling point nearly as powerful as the drink itself.

Consumers now trust Coca-Cola’s identity as much as the taste itself. The secret has created a sense of trust and exclusivity, with people confident that they’ll get the authentic taste of Coke no matter where in the world they are. Now synonymous with American culture, Coca-Cola’s story has become an American secret. Surveys show that a majority of Americans support the formula remaining a secret — citing tradition, mystique, fun, and marketing.

Guarding a trade secret is much more than clever marketing, and it raises important legal questions. What qualifies as a trade secret and how long does that protection last? What happens if the secret is leaked or stolen? How is it different from a patent? These questions are the groundwork for Coca-Cola’s legal story and to understand them, we need to take a look at the laws that keep the secret formula protected.

Legal Implications of Choosing Trade Secrets, Patents, or Both as a Core Intellectual Property (IP) Strategy

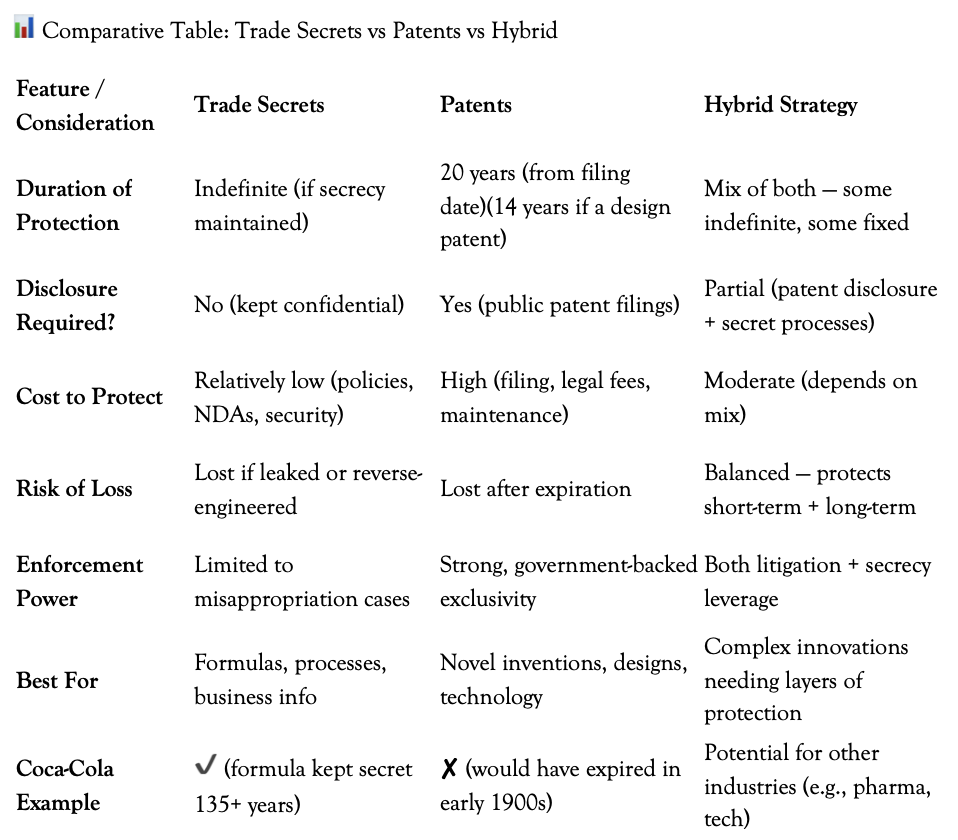

When companies develop valuable innovations—whether a formula, process, or technology—they must decide how best to protect them under intellectual property (IP) law. The choice between trade secret protection, patent protection, or a hybrid of both has profound legal and business implications. Coca-Cola’s decision to maintain its formula as a trade secret instead of patenting it offers a classic example of this strategic fork in the road. Consider the following differences between trade secret protection and patent protection:

Advantages and Risks: Trade Secrets vs Patents

Trade Secret Protection

Benefits:

Protection can last indefinitely, as long as secrecy is maintained.

No registration, disclosure, or government filing is required.

Flexible coverage — applies to formulas, methods, customer lists, and other confidential information — generally, anything that provide a competitive advantage by remaining a secret.

Risks:

Lost forever if the information becomes public.

Cannot stop lawful reverse engineering or independent discovery.

Enforcement can be costly, requiring proof of misappropriation.

Employees and vendors are typically the greatest risks to maintaining trade secret protection.

For a broader discussion of trade secret protection, see our biography post, What are the Basics of Trade Secrets?

Patent Protection

Benefits:

Grants a legal monopoly for 20 years, enforceable against all competitors in the U.S. and other countries if international patent protection obtained.

Provides strong enforcement rights, including injunctions and damages.

·Valuable business asset for licensing, cross-licensing, or raising capital.

Patents tend to be valuable assets for businesses to put on their balance sheet and make acquisition more attractive

Risks:

Requires full public disclosure of the invention before the patent is granted, which is not guaranteed.

Protection is limited in duration (20 years for a utility patent and 14 years for a design patent).

Filing is costly and time-consuming, with strict requirements.

Hybrid Strategy: When to Use Both

For many companies, combining patents and trade secrets is the strongest path:

Patent the aspects of the invention that can be publicly disclosed and will benefit from enforceable exclusivity.

Keep as trade secrets the parts that are difficult to reverse-engineer (e.g., processes, techniques, formulas, or improvements).

Balance short-term exclusivity with long-term secrecy for maximum competitive advantage.

The Coca-Cola story shows that sometimes choosing secrecy over disclosure can secure a company’s competitive advantage for many generations. But for many businesses, the right strategy may be a combination of patents and trade secrets—tailored to the invention, industry, and long-term goals. For a practical discussion of how to apply the hybrid IP strategy approach, see our other blog post, Protecting Recipes with Intellectual Property Law.

Applying Coca‑Cola’s Trade Secret Strategy to Your Business

When counseling clients, I typically begin the patents versus trade secret discussion by focusing on what the public or a competitor can determine or reverse engineer once the client sells its new product or service. If sales essentially disclose the advantage of the product, then patent protection is likely the best IP strategy. If a portion of the invention’s value cannot be discovered post-sales (such as the method of manufacture of a product), then keeping that innovation is typically best protected by a trade secret. Where aspects of the invention are publicly available and undiscoverable, a hybrid approach of dual patent protection and trade secret protection are likely the best option.

Closing Thoughts on Trade Secrets Versus Patents IP Strategy

Coca-Cola is one of the world’s best examples that intellectual property can be as valuable as the product itself. From its humble beginnings as a pain tonic to an international icon, the secrecy of its formula has created brand recognition and loyalty. Coca-Cola made the right decision in choosing a trade secret over a patent, giving it a marketing edge for over 135 years.

But every business, not only those as large as Coca-Cola, has secrets worth protecting — and protecting them correctly can be the difference between becoming an industry leader and falling off the map entirely. We may never know the ingredients in the Coca-Cola recipe, but what we do know: protecting a business’s assets starts with the right IP strategy.

Your secrets may be your business’s most valuable asset.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on Coca-Cola, Trade Secrets, and Patents

Q1: Why did Coca-Cola choose trade secrets instead of patents?

We do not know the answer to this question. However, had Coca-Cola pursued a patent protection strategy, the recipe would have to have been publicly disclosed and the patent would have expired about 20 years later. By keeping the recipe a trade secret, Coca-Cola has preserved exclusivity for more than 135 years.

Q2: Can a competitor legally reverse-engineer Coca-Cola?

Yes. Trade secrets do not protect against reverse engineering or independent discovery. However, despite many attempts, no rival has replicated the exact flavor—and Coca-Cola’s brand strength further protects its market position.

Q3: What laws protect Coca-Cola’s formula today?

The company could rely on at least state trade secret laws and the Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016 (DTSA), which allows enforcement in federal court against misappropriation.

Q4: What would have happened if Coca-Cola patented its recipe?

If Coca-Cola had patented its formula in the late 1800s, the protection would have expired in the early 1900s, making the recipe freely available to competitors.

Q5: Is a hybrid IP strategy ever the right choice?

Yes. Many businesses patent aspects of their inventions while keeping manufacturing processes, formulas, or improvements as trade secrets. This layered approach offers both strong enforcement and long-term secrecy.

Q6: What lessons can other businesses learn from Coca-Cola’s IP strategy?

Every business has valuable confidential information. Choosing the right IP strategy—patents, trade secrets, or both—depends on whether the advantage is publicly visible, easily reverse-engineered, or better protected through confidentiality measures.

Klemchuk PLLC is a leading IP law firm based in Dallas, Texas, focusing on litigation, anti-counterfeiting, trademarks, patents, and business law. Our experienced attorneys assist clients in safeguarding innovation and expanding market share through strategic investments in intellectual property.

This article is provided for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. For guidance on specific legal matters under federal, state, or local laws, please consult with our IP Lawyers.

© 2025 Klemchuk PLLC | Explore our services